the return of phrase books

On Christian Marclay’s The Clock and Georgi Gospodinov’s Time Shelter

If you are receiving this newsletter, chances are you were once a subscriber to phrase books when it was on TinyLetter, a platform that no longer seems to exist but from which I attempted to import the email list to Substack two years ago, intending to transfer it over, and then promptly forgot about. My dear friend Lauren Kane—who runs an excellent newsletter on Milton’s Paradise Lost that you should read—has been after me to revive phrase books for months now, and, well, it’s finally happening.

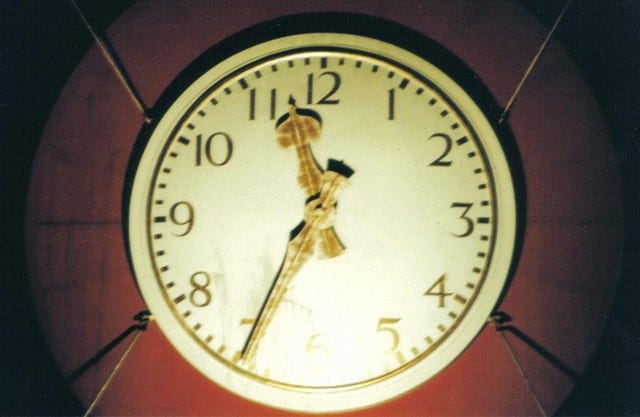

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

What we understand to be time is a fantasy, a technology. A human invention both at odds and in cahoots with the chronology of our bodies and the natural world that surrounds us. Clock time exists as a linear progression: the seconds clot into the minutes that bleed into the hours, the amorphous fragrant hours, that constitute a life. Come spring, nature may regenerate, but humans lack this circularity, this hardy perennialism. We are not plants; from death, we do not grow back.

Nearly a year ago, I bought my first watch in a decade. Nothing fancy: a cheap Timex strung up on a black leather strap. As a teenager in the early 2000s invested in presenting an “eccentric” sensibility to the world, I used to wear a string of three or four of them to a wrist, more a fashion statement, a championing of the analogue over the digital, than any real commitment towards keeping any kind of schedule. Flush with puberty, I was a walking compendium of time zones, my choice in attire an inadvertent throwback to the initial purpose of the watch, that of a lady’s piece of jewelry. (The intended gender of the wearer changed, writes the journalist Dan Falk in his book In Search of Time: The History, Physics, and Philosophy of Time, during World War I, when soldiers took to wearing wristwatches in the trenches.)

Some of these watches that I wore were gifts or hand-me-downs— when I was ten, an aunt passed on to me a silvery wristwatch with planets in place of numbers—but most of them came from the local flea markets or antique malls, of which there existed what seems to me now an unusually high number in my west coast suburban town. When I moved my arm, these watches would clink against each other, tick tock tick tock, and the sound fascinated me, the rhythm of time moving forward without me doing anything to help it. It simply was. I’d think, in passing, about this recycled time, and the other girls, the women, who’d worn these watches before me, adorning themselves with the hours and the minutes, evidence of a life moved in accordance with a present long since in the past.

I bought a watch because I was sick of looking at my phone. A lot of ink has been spilled over these devices, arguing that they are destroying our attention spans, interpersonal relationships, political systems, and daily lives in general, and that’s more or less all true. Smart phones possess the remarkable ability to demolish the artificial guardrails imposed upon us by clocks, but instead of liberating us from the stresses of linear time, they steal our lives away even more effectively than the invention of the second ever did. We once thought it was mechanical time that trapped us: it was the clock, the American historian Lewis Mumford observed in 1934, “not the steam-engine,” that became “the key-machine of the modern industrial age…by its essential nature it disassociated time from human events and helped create the belief in an independent world of mathematically measurable sequences: the special world of science.” But the internet treats time differently: it collapses it, repeats it, surrounds us in its sludge.

In December, I spent two hours at the Museum of Modern Art, watching the Swiss-American video artist Christian Marclay’s 2010 work The Clock. It was not my first time seeing it (it came to Boston over a decade ago, when I was living in Somerville and working at The Baffler), and because it will be on display at MoMA until May of this year, I am also sure that it will not be my last. The work is itself an enormous timepiece: “a 24-hour montage composed from thousands of film and television clips depicting clocks and other references to time,” as the MoMA website tidily explains. But something curious happens as you sit there, watching time pass—the attention paid causes you to lose track of it entirely.

Part of The Clock’s appeal lies in how it interweaves a memento mori sensibility into the pop culture with which we whittle away our hours for the sake of entertainment. The viewer is constantly aware of each minute passing, the abrupt switch from one to another film that will come at the end of sixty seconds. Within the span of time I sat there—from roughly 3:30 to 5:30 in the afternoon, after I had finished teaching the sixth graders I spend my Fridays with—I saw clips from The X-Files, National Treasure, In the Mood for Love, Pineapple Express, Gone With the Wind, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, The Piano Teacher, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Amelie, and a Beatles movie I couldn’t quite place. Catherine Deneuve stood on the platform of a train, waving goodbye as an older woman bid her “Adieu!” Robin Williams hunched beneath harsh fluorescent lighting, developing photos. Julianne Moore clucked her tongue about an email. And then there were the movies I couldn’t place, mostly French and German-speaking fare that I wasn’t sure about. A chess game unfolded in a café. Cities multiplied and refracted. Two men in trench coats spoke in Swiss German to one another before getting in a car, the language incomprehensible to me and yet the tone cheerful, like birds chirping.

Leaving the theater inside the museum where the artwork plays is disorienting. Even though I had quite literally watched time pass before my eyes over the last two hours, I still felt compelled to check the time on my watch once I left and passed from the dark room of the theater, the communal experience of sitting and looking, into the brightness of the museum’s galleries. Confused, I wandered in a circle for a few minutes before I understood where exactly I was going, or that a chunk of time had, indeed, elapsed. Real time is a strange thing to view within a work of art. As the Austrian academic Helga Nowotny notes in her 1989 book Time: The Modern and Postmodern Experience, the invention of “the cinematograph succeeded not just in making pictures move but in slowing down or speeding up the captured moments at will, indeed even in winding them backwards and thus creating totally new ways of seeing.” As viewers, we are so used to film’s manipulation of time—its use of cuts and flashbacks—that to watch images move in accordance with the actual time we’re all living in unsettles us.

But fiction’s propensity towards time travel is beginning to leak into our real lives. Earlier this month, I reread the Bulgarian writer Georgi Gospodinov’s novel Time Shelter, as translated by Angela Rodel, which won the 2023 International Booker. Part of the reason for the reread was that it relates to an essay I’m working on right now for The Baffler, part of it was because it’s a book I’ve recommended to a lot of people over the last few years, and part of it was because it’s still (sadly) prescient about the state of global politics. In it, a philosopher-flaneur—a very twentieth century figure!—starts an unusual Alzheimer’s clinic in Switzerland, in which different floors are accorded and themed around different decades, so as to better help their patients trapped mentally inside their own repeating years. The idea becomes popular, and people without dementia or Alzheimer’s begin to check in. A series of political referendums sweep across Europe, with people voting to turn back time, until finally, the book ends in a historical reenactment of a certain 1914 parade in Sarajevo, that city where the twentieth century as we know it began and ended. I won’t spoil the final pages, but if you ever sat through a high school history class, you probably know how the story ends.

It's a relatively simple, straightforward metaphor, but the results that Gospodinov produces from it are fascinating. Over the last two weeks, the United States and Europe have found themselves, as Time Shelter’s narrator writes of his own timeline, choosing “between two things—living together in a shared past, which we have already done, or letting ourselves fall apart and slaughtering one another, which we have also already done.” Since Donald Trump and J.D. Vance’s terrible display towards Zelensky in the Oval Office on February 28, various European heads of state have grimly announced the need for rearmament. There is a feeling in the air these days of time spinning backwards, certain epochs on the verge of repeating. Though Gospodinov’s portrayal of political time travel leans parodic—the minister of defense an unnamed southeastern country shows up for work, at one point, “on horseback in a revolutionary uniform, girded with a long saber”—the humor is that of the gallows. History does in fact repeat itself—and in this case, it's first as fiction, and then as news headlines.

That famous line of Auden’s from “September 1, 1939”—“We must love one another or die”—is, throughout Time Shelter’s pages, frequently evoked. But as I finished the book this weekend, I thought of another few lines of Auden’s, from “As I Walked Out One Evening”:

“But all the clocks in the city

Began to whirr and chime:

‘O let not Time deceive you,

You cannot conquer Time.’”

Parting gifts

- If you’d like to read some more writing from me about time and literature, I wrote about the first two volumes of the Danish writer Solvej Balle’s septology On the Calculation of Volume (now longlisted for the International Booker!) for The Atlantic in December, and the Italian writer Marosia Castaldi’s The Hunger of Women, with its focus on women’s time, for The Cleveland Review of Books last June.

- Metronome music: As I wrote this, I listened to the 2021 album Timekeeper, a “collection of temporal impressions,” by the Los Angeles-based ambient musician and composer Celia Hollander.

- If you’re in New York, another edition of the Wish You Were Here reading series I run with Kate Peters will be happening on Wednesday, March 26 at Bar Jade in Bushwick. More info can be found on the Partiful invite—please come by!

I am so glad that Substack Reads led me to your essay. Reading it felt like dropping by a salon from another time. I found books I never heard of, connections with watches that mirror and wonderfully expand my own and just a lovely deep dive into this strange present that does feel like a backward lurch of time travel. I look forward to reading more.

Such a wonderful piece. I gave up wearing watches years ago. And now I’ve managed to “waste” 20 minutes on my addictive smartphone reading Substack while time flies!

Not that I need another book, but I’m on my way to ordering Time Shelter, and searching for clips of The Clock on YouTube. On my smartphone. 😊😁